Larry works in an Albuquerque nursing home and like many of its residents he is not thrilled to be at this last-stop warehouse for old folks. Trained as a counselor, he hardly notices the human spirit flowing around him until he meets Bill Foster.

Published: November 2014

Larry works in an Albuquerque nursing home and like many of its residents he is not thrilled to be at this last-stop warehouse for old folks. Trained as a counselor, he hardly notices the human spirit flowing around him until he meets Bill Foster. Bill, a successful clinical psychologist, is lying comatose after a left hemisphere stroke, as Philip Cook, one of his oldest patients, leans over the hospital bed listening intently to his inarticulate attempts to speak.

Through Philip’s uncanny understanding of Bill’s incoherent mutterings, an unlikely collaboration begins, linking the unconfident Larry with the experienced but speech-damaged Dr. Bill. That summer, with Larry’s wife and son out of town, Bill’s counseling practice helps renew Larry confidence as a therapist and--at the nursing home—he starts to see residents, families, and fellow staff as fellow human beings.

But old traumas (the drowning death of his brother and his misplaced blame of his father) run deep: each step seems to open the door for further falls from grace.

This is a novel about disability and the human depth that is left behind after the loss of physical and cognitive faculties. It is also a book about the power of forgiveness.

EXCERPT

Chapter 1

At eight-fifteen on a Monday morning, fifteen minutes late yet again, Larry Whitton pushed open the front doors of Rio Grande Manor nursing home and stepped inside. There wasn't much good to say about his two years working at Rio Grande, but at least it got him out of the stifling New Mexico heat this first day of July. And today, anything that let him forget his own problems for a while was definitely a good thing.

Inside the two sets of double doors common to many Albuquerque nursing homes, he turned to the right around the reception counter and relaxed slightly when he saw that Rita Simpson's door, at the end of the first short corridor, was closed. He then turned left and walked down the long hallway towards the Skilled Unit nurses' station. He walked quickly, all too aware that he needed to drop his briefcase and lunch bag off in his tiny office before Rita could spot him. Aromas of urine and cleaning compounds mingled in the atmosphere that greeted him. Lately he had come to relive these smells in his dreams.

He moved to the left side of the hallway to get around Mrs. Raymond's manual wheelchair―parked dead-center in the grey corridor― before she could reach out and grab his hand. He needed to avoid anything that would proclaim his tardiness to the world.

Seeing Larry, Mrs. Raymond delivered her constant lament, "Help me. Why doesn't someone help me?" Blue housecoat and matching booties her one and only wardrobe choice, Mrs. Raymond was one of those residents who could absorb an hour of your time and not remember who you were five minutes later. Larry, wrinkling his nose, promised to be back, knowing that, whether he returned or not, she would not remember him.

As he passed the open doorway into Mrs. Tartaglia's room, he noticed a green plastic-covered mattress leaning against the wall and Carmen, one of his favorite aides, standing beside it. He stopped, backed up, and tried not to jump to any conclusion. Maybe the old lady just moved down the hall, he told himself. He was about to step into the room and ask Carmen to clarify the situation when, from inside, Rita Simpson's voice, barking as usual, halted him in his tracks.

"That's not my concern, Carmen. Just have this room cleaned, aired, and made up by ten o'clock if you want to go on working here."

He winced. Rita had been the administrator of this nursing home for less than a year, about half the time that Larry had worked here, but it felt like ten years in the Gulag to him. He had seen her fraternizing in resident rooms in only two opposing situations. One was showing the families of potential residents around the facility at which time, all smiles, she would talk about the excellent food, caring staff, and newly installed high-definition TV's. The other was hurriedly removing all traces that a fellow human being had inconsiderately passed on, in order to prepare the vacated room for her next bout of affability. In between those two scenarios, Rita roved the halls finding fault with staff and residents alike. For reasons not entirely clear to Larry, he had somehow attracted her special contempt. Her presence in a resident room made it all too likely that Mrs. Tartaglia had just been launched onward and upward. Torn between anger and sadness, Larry knew that there had been a time when he would have walked boldly into that room, voicing his concern without hesitation.

But now Larry continued down the hall. As he passed the nurses' station, he called out, in a voice that sounded superficial even to his own ears, "Good morning, ladies. Mrs. Raymond, dressed in matching blue this morning, needs a pit stop." The nurse on duty nodded but didn't look up from her clipboard. He went on into the large community room, where several residents were watching TV or staring into space, and saw that Mrs. Wagner was gesturing for him to come over. Frail and nervous, like a small-boned, elegant bird, Mrs. Wagner always had the same lament―the taxi driver had stopped to use a restroom and then had driven away without her. Six years ago, according to her chart.

He waved to Mrs. Wagner―feeling a twinge of sadness for the perverse tenacity of her long-term memory―and reached for his keys. But the door to his office was already open. Irritated, he flung his briefcase onto the chair. A sheet of paper, conspicuously placed on the desktop he had left clean Friday afternoon, announced that Rita wanted to see him immediately. What the hell did that excuse for a human being want now? Was he turning the cage too slowly at Wednesday afternoon bingo? Then another, more welcome, thought hit him. Maybe she had approved his application and wanted to tell him that she had chosen him to be the new director of Social Services.

On his way out of his hole-in-the-wall, he almost ran into Father Cook, whose ample frame leaned heavily on a walker. At six foot three, Larry towered over him by most of a foot, while the priest had thirty pounds on him. Larry muttered, "Give me ten minutes, Father," and tried to get past him before a conversation could develop. He felt badly about putting off the gregarious Father Cook, but the issue of his promotion would prey on his mind until he talked to Rita. If he could go home tonight with some good news, perhaps everything else in his life could be revived also. But Larry cringed as he remembered snapping at his wife over breakfast that morning. All Julie had said was, "Danny and I would love to go out to a restaurant and bowling some evening." He recognized now that Julie was not really complaining about his present salary, even though any entertainment was always at the expense of something else in their tight budget. The deeper problem was that he was sleep-walking through his days, a prisoner of circumstances that he no longer considered himself capable of changing.

"Larry. I'm glad I caught you," Father Cook said, beginning the slow process of turning around in the hallway. Knowing that he could not avoid some kind of interaction, Larry remained in his office doorway while the disabled priest completed his slow pirouette.

"I'm worried about my roommate. Dennis hardly gets out of bed anymore," the father said. "I was hoping you could visit him."

"I'll talk to Dennis later this morning," Larry promised, getting a visual of the young man who had moved in six months before. Then, cutting the conversation short, he continued on toward Mrs. Tartaglia's room in case Rita was still there eradicating all signs of prior human occupancy. He was passing the nurses' station when Carmen came around the corner and grabbed his arm.

"Mr. Larry, did you hear? Señora Tartaglia died last night."

A bare mattress is a bare mattress is a bare mattress.

"I want to go to her Mass this afternoon, but Señora Simpson says I'm too busy."

Larry knew how close Carmen had been to Mrs. Tartaglia and his jaw hardened, but before he could respond Señora Simpson herself was suddenly on top of them, her pale eyes glowering up at him. "I see you finally made it in, Mr. Whitton," she said. "I need to talk with you in my office immediately."

"I need to speak with you too," Larry managed, as Rita spun around and charged down the hall toward her office. With her close-cropped blond curls and compact body, she reminded Larry of a yappy in-bred poodle. The kind that draws blood when they snap at you. He continued in her wake, seething with resentment toward her but even more angry with himself for allowing her to get to him.

Rita was already seated at her desk when Larry caught up and entered her office. "We have a new staff member," she told him, before he had a chance to close the door. "I'll be announcing it tomorrow at the staff meeting, but it affects you in particular."

"I've been meaning to ask you about my application for the director position," he blurted out.

Rita looked at him blankly. "What are you talking about?"

Larry leaned forward and launched into his well-rehearsed speech. "I haven't heard back about the Social Services director position I applied for last month, and I'd like to know if I'm still in the running."

"You applied? Rita said, apparently caught off guard. Then, quickly returning to her snappy indifference, she continued. "You aren't qualified. The new director I hired has an LMSW."

"I'm a Licensed Master of Social Work!" He managed to get out, as it slowly sunk in that his dream of getting a decently paid job had died at the starting gate.

For a brief moment, Rita appeared genuinely amazed, and Larry, hardly able to breathe, stammered, "You mean I've been waiting for three weeks and you didn't even know that I applied! And you've never known that I'm an LMSW?"

"You'll be reporting to Ms. Hildie Gallegos, our new Social Services director," Rita replied, as if she hadn't heard a word of what Larry had said. Then, with an icy smile, she added, "Look on the bright side, Mr. Whitton. Now you'll have two bosses to mock at staff meetings."

Larry stood up shakily, walked to the door, and stepped out into the corridor. Taking each step deliberately, he made it back to his office. Once inside his own little space, he closed the door and switched off the light.

The memory that invaded Larry's mind was not from a morning half a year ago, when--with incredibly poor timing--he had imitated a dog walking on two legs and talking in a shrill voice about staff time squandered on bingo for residents. The memory that lay there now, like undigested food, was of Julie crossing their front yard that morning. Her silence at breakfast had not boded well, and, as she approached the Honda, its engine already running, her deliberate steps told him that some long-suppressed message was about to be delivered.

"Our marriage isn't working," she had announced.

Then she had turned on her heel and run back into the house. Perhaps he should have returned to the house right then and talked it out a bit. Rubbed her shoulders, promised that things were about to turn around. But he had barely found the strength to back the car out of the driveway and get to work a mere fifteen minutes late.

A knock on his office door brought Larry back to the small, darkened room where he sat with his eyes closed. He stood up, switched on the light, and squinted in the sudden glare. He was about to open the door when another memory came back to him, of something Julie had said to him about a year ago. "You need to forgive your father. If you don't, you'll end up just like him."

Really? How exactly did coming home every night after a miserable day at work resemble bailing from your son's life when he's seven years old--as his own father had?

Larry swung open the door and saw Father Cook--now seated in his wheelchair and no longer wearing the prosthetic limb on his left leg stump--blocking the way. "Have you visited Dennis yet?" the priest asked.

Larry was about to beg off when the words froze deep in his throat. Julie was right. He was turning into his father, always running away from intimacy and the pain that came with it.

"Let's go look for Dennis," he heard himself say.

Father Cook turned his chair around and wheeled off down the corridor in the direction of the room he and Dennis Simmons had shared for the past two months. His arms were strong and he could roll himself around the nursing home most days. Although in the wake of the massive heart attack that had sent him to Rio Grande years before Larry's arrival, the priest's amputated leg was monitored closely by the medical team. At least he's not losing ground every day like Dennis, Larry realized.

Glancing back at the north nurses' station, Larry saw Rita bent over a chart, her head jutted forward as if she was about to bite the folder and shake it side to side. A resolution formed in his mind. He would find a new job, become a better husband and father, and get his life back.

They found Dennis up and in his wheelchair. Or rather, they found him slumped over in his chair, looking uncomfortable and exhausted. Dennis struggled to sit up straighter as they entered the room, but his whole body trembled with the effort, and then he still looked off-balance. It passed through Larry's mind that Dennis would not be able to use his lightweight manual chair much longer. Hadn't he been using a walker when he arrived at Rio Grande Manor a few days into the New Year? Since then his multiple sclerosis had progressed with devastating speed.

"Larry's here to see you," Father Cook announced in an enthusiastic voice. Larry couldn't help noticing that Dennis didn't seem to share this enthusiasm. In fact, Dennis's face remained averted, as if he had resolved to deny reality by ignoring it.

Larry felt a surge of empathy. Dennis was probably, like Larry, in his thirties, and here he was forced to end his days in a nursing home. He wondered if Dennis had a family from which his progressive MS--as was so often the case--had banished him. Voicing this thought, Larry turned to Dennis and said, "Where did you live before coming to Rio Grande Manor, Dennis?"

Even if Dennis had been willing to answer this question, he didn't have the chance. Rita appeared in the doorway and, without so much as a glance toward Dennis or Father Cook, said, "I need you to write a job description for your new boss. And I need it on my desk before the end of the day!" Then she vanished into the hallway.

He was glaring at the empty doorway with loathing when, out of the corner of his eye, he caught a movement from Dennis's chair. He turned just in time to see that Dennis had slid precipitously to one side and that the armrest was gouging him in the ribs. Larry quickly moved behind the wheelchair and pulled Dennis up.

Here it was scarcely mid-morning, and Dennis couldn't stay upright in his chair. Father Cook must have been thinking the same thing because he said, "Dennis needs to lie down."

Larry nodded, adjusted Dennis's foot, which was ready to slip off the foot rest, and promised to visit later. On his way out, he pushed the call light beside Dennis's bed, so that aides trained to transfer residents could come and put him in bed. Part of him felt like ignoring Rita's request to write up a job description, but then he decided that it was probably one of the few things he could manage right now. He went back to his cubicle and typed out a couple of pages about the Activities Coordinator position for which two years of study and his LMSW had prepared him to be overqualified.

Around two that afternoon, he taped a note to his door that he was out sick, dropped his job description off at the front desk for Rita, and left the building. Tomorrow he would throw himself into the task of trying to help residents remain active and involved in their sad lives, which for many had turned south the moment they had walked, or been pushed, through the doors of Rio Grande Manor--lives that for some would include no further ventures into the world until the day they left with a sheet pulled over their faces. But that would be tomorrow. Today he needed to plot his escape from this Gulag and its Commandant.

In no hurry to tell Julie the bad news about the non-existent promotion for which they both had hoped, Larry stopped at Einstein Bagels, picked up a coffee and newspaper, and for the first time in over a year turned to the want ads. Thirty minutes later, his third cup of coffee turning sour in his stomach, he got up and stuffed the newspaper into a trash can. Nothing. Maybe he'd try Googling jobs that evening, if he could muster the energy.

He drove home and found Julie in the living room reading from a picture book to their five-year-old son. Danny seemed interested and focused, something that they hadn't been able to count on in recent months.

Julie looked up, surprised to see him home so early. She still seemed beautiful to him after all these years, her light brown hair swept back from her strong, tanned face. Not knowing what else to do, he sat down on the armchair beside the couch and told her about his disastrous meeting with Rita. When he had finished, he had trouble keeping eye contact with her. It had taken Larry a year to find work after getting his social work degree, and they both knew that quitting Rio Grande Manor without a new job lined up was inviting disaster. Danny sat quietly, looking from one to the other.

Finally Julie spoke. "Maybe it's time to look for a different job, Larry. Who was that guy who said you should be a counselor? You went to Highlands with him."

"Sammy Sanchez. Why?"

"Isn't he in private practice here in town? And didn't he tell you that you had the capacity to be a great therapist?"

Larry sighed and shrugged. What did Sammy Sanchez have to do with them? So he had studied with a classmate whose life was dazzlingly successful. Was Julie trying to rub salt into his wounds? Why mention Sammy now, in this moment of deep humiliation?

Julie stood up, and said, "Call him." Then, with Danny, already tall for his five years, two steps behind, she went outside.

Larry followed Julie and Danny as far as the back patio, and watched them pick weeds from among the tomato plants and patches of basil. A sudden gust of wind sent a cloud of sand from the neighbor's yard over the cinder-block wall. Larry closed his eyes. It had been humiliating looking for work last time, but now something even worse had slithered into his life. His family wasn't going to survive if he didn't change something. Julie was right. Another summer at Rio Grande Manor nursing home, coming home every night angry and resentful, and he would turn into the kind of husband and father his own father had been. But how could he call Sammy? How could he consider, for a single instant, risking the life of someone who would come to him, in pain and confusion, looking for counsel and help? One innocent life down the drain, as had happened in his second year of graduate school, was already one too many. The memory of that loss was still too vivid.

He heard Danny ask Julie if something was a weed, but Larry kept his eyes closed and went back twenty-four years in time to the day his father had returned from a canoe trip, alone. Timmy, Larry's older brother, only nine years old, had just drowned. A month later his dad had moved out, and from that day on his mother had never once hugged him. If she looked at him at all, her eyes said, "Why couldn't Timmy have survived? He was the one I loved."

Sometimes Julie acted as if she thought she needed to rescue Danny from Larry. Some evenings Larry would get a reflection of how deeply immersed he was in his own private depression when Julie would suddenly take Danny and leave the house. Larry worried about his black moods. Recently Danny had developed some distressing habits--staring into space and responding very slowly to questions. But surely Danny knew that both his parents loved him. It wasn't like Danny's dad had walked out on him and his mom couldn't bear to look at him.

Meanwhile Julie's parents--who made no attempt to hide their disapproval of Larry--were waiting in the wings, ready to rescue their daughter and their grandson. Not for the first time, Larry wondered if Danny might actually be better off without him.

He felt small hands tugging at his pants, and his son's voice asking, "Why are you home so early today, Daddy?" Larry, his eyes stinging, bent down and lifted Danny into his arms.

After supper, while Julie was reading a bedtime story to Danny, Larry made the dreaded call. Relieved when Sammy's answering machine picked up, he blurted out something about working as a counselor. But later that evening, when Julie asked him if he had said he was looking for work, Larry couldn't remember if he had actually said so out loud.

Goodreads ** Amazon ** Barnes&Noble ** Kobo

About the author:

Before coming to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he now reside with his wife and two sons, Michael Gray lived in Montreal, Canada and published short stories and poetry in the Antigonish and Wascana Reviews. He traveled in Europe for six months and South America for three months, but it was while working on farms, ranches, and an open-pit copper mine in Canada that he heard a door into the future creak open.

Before coming to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he now reside with his wife and two sons, Michael Gray lived in Montreal, Canada and published short stories and poetry in the Antigonish and Wascana Reviews. He traveled in Europe for six months and South America for three months, but it was while working on farms, ranches, and an open-pit copper mine in Canada that he heard a door into the future creak open.Michael’s memoir, The Flying Caterpillar (ABQ Press, 2012), as well as being a travel log of his life to-date, gives an account of his two decades with Friends in Time and explores the teachings and encounters which have proved to be valuable for a lifetime. In 2012, he also published Asleep at the Wheel of Time (ABQ Press), a SF novel about Whales, Aliens and humans. Both these books express his concern about the state of planet Earth in light of our accumulating indifference to the plight of our only home.

Michael’s newest novel, Falling on the Bright Side draws directly on his experience working with the disabled (For more than five years he’s also been President and sometimes ED of Pathways Academy, a school for kids with Autism and other learning issues). Falling tells the story of people who have been shelved in nursing home warehouses, or have otherwise lost their livelihood and value to society, and the narrative arc explores how the human dimension continues to shine in these human beings.

In his own life Michael has discovered that people who are in the process of losing their identities, occupations, and old friends are able to help him recognize a deeper truth about the human predicaments they share. This is a human truth which he also finds celebrated in Eastern spiritual teachings. Encountering the core of humanity in people whose familiar lives have dissolved, he seeks to learn their secret while he still has time on my side.

Author's Giveaway

a Rafflecopter giveaway"As I began to read this book I became enthralled by Mr. Whaley writing which had pulled me in effortlessly to the literary fiction which the author states on GoodReads.com for the book’s description is based on a true family saga." - Goodreads, Robin Leigh

Published: July 2014

After a forty-year-old secret is exhumed from his parent’s tumultuous marriage, Benjamin Sean Quinn boards a plane to Billings, Montana to face the secret head on and let go of the anger for them that silently ruled his life. It would be the boldest move he ever made, ultimately changing his life and the lives of those around him. Compelling literary fiction based on true family saga!

Leaving Montana is the recipient of both the 2015 Eric Hoffer Award for a Small Press Published work and also the 2015 National Indie Excellence Book Award for Literary Fiction!

"For those of you looking for a truthful birds eye view, into a complex family dynamic, that spills over with layers of chaos and turmoil, you've come to the right place. This is a story of a boy lost and found, on his journey to heal from his painful past." - Joan Dash

EXCERPT

Chapter One

My bags were already packed. I had made sure to put them in the car the night before, so I wouldn’t disturb anyone. The alarm was set for three in the morning, but I had already woken up. I shut it off. Waking up before the alarm was something that happened to me often, especially when it was an important day. Growing up, it was always the first day of school, or my birthday, but as I aged, it became quite common. I enjoyed lying in the darkness, listening to all the subtle sounds a sleeping house makes. It was soothing, but these were also the moments when I thought too much. And, I already had a lot on my mind.

My partner and two daughters were fast asleep, as I quietly prepared for the monumental day in the soft light coming from the master bedroom. I had been waiting almost two years for the day to arrive. Making these particular plans come to fruition had not been easy—especially for someone who was used to being quick and efficient. It was the day I opened the door, and emptied “it” out. Well, almost. It would be another day or two before I had the chance to empty “it” in its entirety, but the door was ajar. That was the most exciting part.

Having already showered the night before, I quickly rinsed myself off and fumbled around the bathroom, getting ready.

The master bathroom was tight to begin with, and trying to be quiet made it seem even smaller. Our shower was the stand-up kind. It was like being in a test tube, and my elbows kept hitting the oversized shampoo bin, suctioned cupped to the side. Every drawer I opened, and each item I placed on the counter, made a louder noise than usual, but I wanted to make sure I looked perfect for the trip.

I slipped on my favorite pair of broken-in jeans, a maroon hoodie that I had gotten on a family trip to Maine a few years prior, my running shoes, and a ball cap. I had already laid out everything on the ironing board before I went to bed. It was going to be a long day of travel, and comfort was key.

I made sure not to dig too deep in my massive, walk-in closet. Only the things that I found easily came with me. This proved to be a very difficult process. Being a certified clothes whore (and proud of it, I may add), made it extremely hard to decide what to pack. Would I need something dressy, in case we went out to a nice restaurant? Did I need a classy sweater? Do I pack a pair of dress shoes just in case? A matching belt? This caused me stress every time I traveled, but this time, not having to dress like a professional made me happy, and somehow, it was easier to turn down all the accessories calling my name.

Faint, distant beeps from the coffee maker invited me from down the hall, into the kitchen. I inhaled the potent Columbian fragrance like a pothead inhales dope. The intense aroma always made me smile, but today, it needed to be especially strong—something that would keep me alert. Focused. Calm. Saying I had a severe addiction to coffee was an understatement. It had been a staple in my maternal grandparents’ house, where I spent most of my time growing up. Memories of my grandfather, encouraging me to sip espresso from his tiny cup, as I sat on his heroic lap, came to mind each time I experienced a really good cup of Joe. By the age of nine—I was hooked. And straight up too. Never a drop of milk, and always unsweetened. What I like to call a “real” coffee drinker. Naturally, I was not allowed to drink it in front of my parents at such a young age, but like any child, I was a great sneak.

Last time I drank too much coffee on the way to the airport, I was forced to get out of my car and pee in the middle of traffic, so I made sure to hit the bathroom one last time before leaving.

It was a bitter, December morning, so I enjoyed a cup while my car warmed up. It had been an especially cold winter, and we’d already had well over 36 inches of snowfall on Long Island. A blizzard had dumped nearly 20 inches two weeks prior, so our house still had tall snow walls along the walkway to our front door, and the edge of the driveway. Underneath all that snow and ice were my hibernating English-style gardens. Knowing I would nurture and appreciate them sometime soon was the only thing that got me through the winters.

Gardening is one of my passions. Dirt calms my nerves, and whenever I felt anxiety rising, I would head straight to the local nursery. My gardens are the gifts that kept on giving, like my children. From the very beginning—when they are fragile and new, you get to nurture and shape them, hoping they eventually grow to be strong and independent.

A green thumb was one of the very few positive things that I had inherited from my paternal side. My paternal grandfather loved gardening. From as far back as I can remember, his gardens were the most exquisite. Blooms of all shapes and sizes, bursting with sweetness, and attracting a multitude of bees and butterflies. I would sit and stare. I often wished I could live inside one of his gardens. It was quiet there. When he passed away, his gardens died along with him. I would like to believe I am his apprentice, but to this day, I still cannot grow peonies the way he could.

It was not that cold on Long Island—not compared to where I was heading. That was the only downside to the journey. I despise snow. I loathe it. And the cold? Unless it is a cold shower, or a refreshing pool on a ninety-degree day, I am not interested. Layers, chapped lips, and wet, cold, wrinkly-gloved hands are not for me.

I am a summer kind of guy. Give me a lawn chair, a cold six-pack, the roaring sun, and by four in the afternoon, I’m a new nationality, ready to sport a crisp white pair of shorts to show off my bronzed skin and great calves. Although cold weather and bulky layers bothered me, I was more than willing to wear three layers for the occasion.

I was already running late. I couldn’t procrastinate any longer—especially since it was the only flight of the day that could get me to my final destination. Although I was traveling within “The States,” not many New Yorkers had reasons to travel to where I was going. But I did. The trip required precise planning, and there was a connection. So if I missed the first flight, I was screwed. Needless to say, I picked up my backpack and added my dirty coffee cup to “Clutter Island” in the center of my kitchen, rather than putting it into the sink only steps away. Laughing to myself, I made my way down the hall and walked out the front door, gladly forgetting about the mess.

The car ride was tranquil. Hardly anyone on the highway. No questioning children in the backseat, and the sounds of Simon and Garfunkel, and The Carpenters playing from the radio. I had put those CD’s in the car stereo a few days earlier, and now I was truly appreciating that I did. Both had number one hits in 1970. I didn’t exist yet, and everyone was still clean back then.

I loved music from the 70’s. All the songs somehow had lyrics you could relate to. I knew exactly which singers from the 70’s to listen to at specific times. Barry White, for the times when I liked what I saw staring back at me in the mirror. For summer BBQ’s, and trips to Fire Island—Donna Summer was a must. Pink Floyd, for when I felt the need to drown myself in booze, or lock myself in a dark room. Whatever the emotion—I had the 70’s to run to. I truly believed that anyone who was born in the 1970’s was conceived in lust, rather than love.

I know I was.

By the way, let me formally introduce myself. I am Benjamin Sean Quinn. Forty. Confidently handsome. Sexy, as I’ve frequently been told. And a damn good advertising executive. I have a fantastic, caring and supportive partner of 14 years. My home belongs in a Pottery Barn catalog. We live in a prestigious neighborhood, and our two adopted daughters are perfect in every way…but there’s one small problem.

I am angry as hell.

Angry to the core.

Most people would question, “How could someone with such a pleasant and obviously privileged life be so angry?” Most people would, in turn, firmly state, “What an arrogantly pompous, self-appreciating, douche bag!” especially based on the way I just described my life, and myself. It is all true. I admit that whole-heartedly. But, I deserve to be. Now, you may think that no one deserves to be so self-appreciating, but I beg to differ. Growing up in a toxic environment that you have no control over forces you to make a choice: adopt that pattern and sink to the bottom, or swim like a motherfucker. I chose the latter. I am an awesome swimmer.

I wonder if ALL of us have experienced toxicity in our youth—the kind that leaves us branded. But unlike cattle, being scarred with a symbol from a branding iron, it leaves a word on our

foreheads that only certain people can see: SHALLOW, VAIN, NAÏVE, SLUT.

Personality traits we try to scrub away, or cover up when they surface. Isn’t there at least one undesirable personal trait you blame your parents for? I believe you can. If you are someone who has not internally blamed your parents, or at least one of them, for one, or more of your shortcomings, then you must have grown up in a utopia.

It is natural to blame your parents. Everyone does it. It is an unavoidable cycle. We are timid, because our mothers were too overprotective. We have anger and abandonment issues, because our fathers were unloving and never available. We have issues with commitment, because their marriage was a bad one. Who knows what the reasons are. But they are there, lurking deep within.

Blaming my parents for ruining my childhood, and branding me POMPOUS, ARROGANT, SARCASTIC, and God knows what else, is an understatement. I often overhear people complaining about the ridiculous things their biological breeders have done to them, and I laugh inside. “Big deal,” I’d say under my breath, hoping they’d hear. “Come on! You’re still upset with your mom for not letting you go to prom with what’s-his-name?” Put that petty shit away already. Let it go. It doesn’t matter anymore. Not to mention, it is trifling. Believe me, I know. When you have accumulated the amount of emotional baggage that I have, and yes, I DO blame my parents for it all, then you really can’t just forget it. You cannot let it go. You store it.

This is why I like walk-in-closets.

I LOVE my walk-in-closet. It has plenty of storage.

Lined with spacious shelves, deep drawers, shallow drawers, hanging poles of various lengths, and tiered shoe racks—it truly rocks my world. When I stand inside and look around, I see my entire life before me. So many things from my past, yet ample space for my future. It is conceited.

I am a walk-in closet.

I am polished, refined and perfectly coordinated. A private clothing boutique on Fifth Avenue, with Italian cashmere sweaters. I am Calm. Collected. Confident. But in an instant, one thought from my childhood can transform me. I am Disorganized. Wrinkled. Torn.

I am dirty clothes twisted among clean. A confusing jumble of belts, shoes, pants and hats on the floor. Socks stuck in sleeves, ties still knotted, and things inside out. Scattered feelings, and emotions that cannot be sorted out, picked up, washed, or turned right side in.

I am a walk in closet—and just like a walk in closet, when your poles begin to bend, and drawers cannot close—we realize that we have accumulated way too much.

Listen closely, friend…. there comes a time in everyone’s life when we hit a crossroads, faced with some of the most difficult decisions we ever have to make. Do we open our closet up and finally clean it out? Or do you close the door and pretend it isn’t a total mess? I wanted to open mine. Carmella and Sean chose to close the door and ignore it. I chose to board a plane. When I left the house, I did not close the door. Anyone could peek inside. The effect could cause an emotional catastrophe. But I chose not to care anymore.

Finding a parking spot at JFK was a pain in the ass, even at five o’clock on a Thursday morning. I lowered the radio, as if that was going to interfere with finding a parking spot. Do you ever notice yourself doing that? Randomly lowering the volume for no apparent reason? I do it all the time.

I focused on all the makes and models of the cars and trucks. It was truly astounding. When you live in a neighborhood full of Range Rovers, Mercedes, BMWs and Saabs, you forget the variety. There was a perfect match for everyone. Imagining what the owners of the vehicles looked like, and where they went, proved to be a humorous way to pass the time while searching for a spot.

Did any of them resemble their cars? You know—the way dogs and their owners eventually morph into one? I slowly approached a brown, oversized, slightly beat-up Yukon, which practically took up two spaces. I noticed that a piece of the side view mirror was missing. Evander Holyfield? Maybe just a coincidence, but uncanny none the less. There was also a meek, bullied Toyota next to it. It was missing a hubcap, which in my opinion, is the most unattractive thing about older cars. Hubcaps. Dented, rusted, MISSING. Replace the damn thing! If your shoe falls off, do you just walk around wearing one? Precisely.

Greenish. I stared at it for a second. I guess you would call it teal. No automobile should ever be teal. Ever. Or light yellow. Anyhow, after getting slightly annoyed and distracted by the hubcap, I noticed it had a Reba McIntyre license plate cover on the front. Obviously, this car had much bigger issues.

I stared at it. A concert souvenir, no doubt. The car immediately transformed into the owner. A pear shaped, tall, amazon-like woman, in her mid to late fifties. She was stuck in the 80’s—with big, blown out, Ronald McDonald colored hair. She had split ends, but her friends were too nervous to tell her. She was probably on her way to some “I Am Woman, Hear Me Roar” convention. I began to frown, and when I looked into the rearview mirror, I noticed that my head was gently moving side to side in disgust. This very reaction happened to me quite often. I am shocked that it hasn’t brought me any bodily harm yet. This caused me to laugh out loud and drip some coffee on my seat.

I quickly pulled over and got out of my car to wipe the coffee off my seat, before I ended up looking like I shit myself. I was still laughing. It felt good. It was the first time I had genuinely laughed recently. Feeling nervous was foreign to me. And although I was very excited about the trip, the unknown was still frightening. Things didn’t usually bother me; my skin was thick as a rhino’s. Inherited, I guess. Earned? Absolutely.

White lights. Someone was leaving. A flashy new, black Escalade dripping in chrome, was now backing out. It resembled a drug lord’s ride. I was immediately intrigued. True Long Islanders are drawn to shiny, black Escalades like moths to a flame. “Thank you!” I mouthed to the mysterious driver with my thumb up. Again, similar to turning down the volume on a car radio for no reason, I wondered why I was “mouthing” to my hero—speaking through the glass without volume. I do that often too, and I never quite know why.

My mysterious parking spot friend was a gorgeous well-dressed Latino man. I had one word. YUM. His hair was long, wavy and slicked back. Although it was still dark out, he was wearing sunglasses. His shirt— white and crisp. I was impressed. Impressing me was hard to do. I also noticed the sparkle of his diamond cuff links. This sparked a fire. He was pure cocaine.

I hope his trip to Columbia was as enjoyable as my coffee.

When I get to an airport, there are three things I look forward to doing: Browsing the magazine shops in search of some quality literature, getting myself a large cup of coffee, of course, and finding the right seat to people watch. It is one of the best places to truly appreciate the art of people watching. Airports and malls. Ample seating. Perfect for shallow, self-absorbed people to judge.

Upon finding the perfect spot, I made myself comfortable.To my dismay, there was a lack of interesting people, so I decided to enjoy my coffee and quality literature. Men’s Health, Vanity Fair, and GQ. What did you expect? Shallow. Need I keep reminding you? These magazines kept my stomach flat, my wardrobe up to date, and my sex life smoldering. A gay man’s guide to a perfect life.

My backpack had all the essentials for a day of travel, and my magazines were only a portion of them. The most important thing in my backpack was my crossword puzzle. I was addicted, especially to the one in the back of The New Yorker. To this day, I am still not sure why that particular crossword from that particular magazine brought me the most joy, but it did. I don’t even read the content. It would require too much concentration. Sitting down with a pen, and having the uninterrupted time to work on one is better than jerking off to any DNA magazine photo spread. And yes, pen. Would someone as overconfident as I use a pencil? I think not.

It was time to board. 12D, an aisle seat. This was the only way to fly. To be crunched between two fat asses would make anyone cry, and I needed legroom. Plus, with the amount of coffee I had already consumed, a bathroom needed to be easily accessible.

As instructed by Flight Attendant Barbie, I placed my perfectly worn, leather carry-on bag in the overhead bin, and then I organized my array of quality literature in the seat pocket in front of me. After fumbling with my overstretched, tangled seatbelt—from the oversized passenger that had been on the flight before me, I tested out my pen, by scribbling a mini-tornado on the cheesy, airline mall magazine.

While Barbie informed us that our flight was going to be leaving soon, I caught myself humming The Carpenters. I bet my parents, Carmella and Sean, heard We’ve Only Just Begun by The Carpenters on their way to Montana—just as I had on my way to the airport. Although there was a forty year span between our visits, we all personally connected with that song during that moment in time. Carmella and Sean had only just begun their lives together. With each mile closer to Montana, Sean’s control began to gain power and momentum. As for me, I had only just begun finding closure.

The stewardess began reciting her script, her voice reminding me of the schoolteacher in Charlie Brown. I looked around. No one was paying attention. Oxygen. Flotation devices. Blah. Blah. Blah. We all knew that if we went down, that shit wouldn’t work. Picking up my crossword, I noticed my ink tornado on the cover.

I smiled.

That tiny tornado was me.

Goodreads ** Amazon ** Barnes&Noble

About the authors:

Thomas Whaley was born in 1972 and has lived on Long Island his entire life. He is an elementary school teacher and has always enjoyed writing as a pastime. Thomas currently lives in Shoreham, New York with his husband Carl, their two sons Andrew and Luke, and loyal dog Jake.

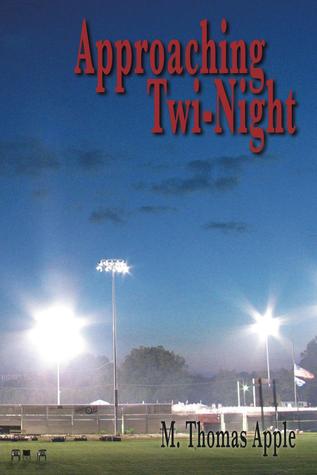

An aging baseball player is given one final chance at professional and personal redemption in small town America as he struggles to come to grips with his past, his sense of self, and his career.

Description:

Description:Published: February 2015

An aging baseball player is given one final chance at professional and personal redemption in small town America as he struggles to come to grips with his past, his sense of self, and his career.

Journeyman relief pitcher Jonathan “Ditch” Klein was all set to be a replacement player during the 1994-1995 baseball strike…until the strike ended. Offered a contract in the minor leagues, playing at the same Upstate NY ballpark he once found success in high school, Ditch has one last chance to prove his worth. But to whom?

A manager with an axe to grind, a father second-guessing his pitching decisions, a local sportswriter hailing him as a hometown hero, a decade older than his teammates and trying to resurrect an injury-ridden career…Ditch thinks he may have a possible back-up plan: become a sportswriter himself.

The only question is whether he is a pitcher who aspires to be a writer, or the other way around…

EXCERPT

From his perch on the mound, Ditch shaded his eyes and watched the foul ball gently curve over the grandstand toward the parking lot. As he held his glove out for the new ball, he could hear his father's voice from a high school game: "Straighten that out, Johnny, just straighten it out!" And he could remember himself at the plate, thinking, "I can't, Dad. I can't hit it."

He gripped the dull white leather in his pitching hand, tucked the glove under his left arm and slowly circled the mound. Ditch's hands worked the leather, trying to deftly massage life into the ball. His fingernails found the seams and began to pull them up from the leather; Ditch had always wondered as a kid why pitchers on TV wasted so much time walking the infield grass, if "raised seams" actually did anything to curves like his father claimed, if pitchers who stared out at the crowd were actually looking for someone. He stopped on the first base side of the mound and glanced at the runners on first and second, not really to check on them, just let them know he knew they were there. The runners strayed a step or two from their bags, sauntering back and forth with hands on hips, kicking the bags a couple times impatiently. They knew Ditch wouldn't throw, he knew they wouldn't run, not on Holforth's arm.

Ditch tugged at his cap and deliberately ignored the anxious hometown crowd on "Opening Day Two." Absently he wondered if his family was in the stands somewhere, his father holding little Jennifer up on his shoulders, pointing, "There's John, there he is." He climbed back up to the pitching rubber, haphazardly pulling his short sleeves up and shrugging them down again. The murmurs changed to a soft buzz of rushing air in his ears as he dug in with his right foot and stared in at Holforth behind the plate. He squinted on purpose at the flashing fingers, set for the third pitch, and threw.

The batter fouled it off again, this time straight into the visiting team dugout, nearly hitting the coaches at the top of the steps. Ditch received the next new ball and began his ritual anew. The batter fidgeted, stepping out of the box with one foot and nervously swinging his bat a few times and changing his grip as if he were uncomfortable using wood instead of aluminum. Ditch looked at the wispy clouds overhead, the one-two count in the back of his mind, and decided to waste a pitch.

Holforth almost failed to block the errant pitch, but he managed to smother the forty-foot curve, hurriedly flipping his mask off and alertly checking the runners back to their bags. The catcher turned to ask for time, and Ditch turned his back on the plate. Holforth was bound to be angry. He knew Holforth hated it when his calls weren't taken seriously. He tugged his cap and kicked at his trench.

The catcher pulled the ball out of his mitt and placed it in Ditch's. Holforth darted a look at the vacant right field foul line bullpen, then back at Ditch. "You can let go now," Ditch said. "I've got it."

Holforth withdrew his hand from the glove. "Inside and high," he stated. "This guy's never used a wooden bat before." He turned back to the plate and pulled his face mask on over his hard hat. Neither have you, Ditch thought, already pacing at the back of the mound, massaging the ball. He found the soft spot, brown from the last pitch. The Majors spoiled their pitchers, he thought. They want a new ball, they get one. Even now, he knew, a batboy was rounding up the foul balls in the dugouts and along the foul line, ready to hand them over to the plate ump between half-innings. He randomly glanced at the rust-green electronic scoreboard with the Pepsi label slapped on it in left-center field. A two-run lead he was supposed to protect, for the last two innings. Collins had made that clear; Ditch was on his own. He felt the urge to spit, then changed his mind, then did it anyway. What the hell, he thought, pushing his sleeves up again.

He stepped up again and caught the signs. High and inside. At the hands. He checked the runners, reared, and threw at the batter's head. The kid ducked as the ball flew at the backstop. He could hear Holforth's muffled curse as the catcher futilely flung his glove hand back and followed it with his body. Ditch loped to the plate to cover, but the runners stopped at third and second as Holforth got the ball back in play. Someone in the crowd behind third base booed, but his neighbors quickly hushed him. Ditch cleared the dirt around the plate with the tip of his shoe and tugged again at the hat. He headed back to his incantations. The infielders hesitantly moved back to their positions, pounding their gloves and muttering nearly inaudible words of encouragement. A hit would tie the game. Ditch let his sleeves fall down as he mounted.

Holforth was standing right in front of him. Ditch betrayed no surprise. "You're making me look bad, man," the catcher said tersely. He rubbed the sweat dripping down his chin onto a sleeve. "We can't do that again, so I want you to throw the pitch."

He shook his head and dug at the trench. Holforth called it "the pitch," as if it were a secret weapon of some kind; he wanted the awkward slider he made Ditch work on in the bullpen, the one he could throw with the bent finger underneath. He hated it. He hated using a trick pitch.

"I'm telling you, do it," Holforth repeated. "Cut the crap and get this guy." He turned abruptly and trotted back to the plate. Ditch placed his right foot behind the rubber and looked up. The other ump had moved to behind third base. Only two umpires in this league, Ditch remembered with a chagrin. He looked in at the plate and jerked his head back to third as he faked a throw. The runner froze, then looked embarrassed, realizing that the third baseman wasn't anywhere near the bag for a pick-off throw. Ditch smiled to himself and tugged at his cap with his ball hand. The third baseman edged towards the bag, pulling the runner closer. Ditch paid the two no mind.

He looked back in. Holforth signaled for the pitch. Ditch shook his head. Holforth signed for it again. Again, Ditch shook it off. Exasperated, Holforth audibly slapped his thigh. He angrily flipped down a single finger. Ditch laughed out loud. The batter called time. Ditch stepped off and put his head down. He could hear the plate ump say, "Let's go gentlemen." Gentlemen, he thought. Yeah. He watched the batter take a few more swings, adjust his helmet without adjusting it at all, and then step back in. The crowd noise briefly interrupted then seemed to recede.

He looked in and he saw Holforth stand up and adjust his cup before squatting again. Ditch turned his head to peer at the runners momentarily, then turned back and got the expected signal. He didn't respond. The signal came again, insistent. He lowered his head, and stood, hands ready at his belt. He could sense Holforth settling back, the ump crouching behind with a hand on Holforth's shoulder. The bent third underneath and two forefingers on the seams, he withdrew his hand from the glove. His wrist snapped out and down, and the ball spun towards the batter's waist. It seemed to rise and curve left, directly into the batter's wheelhouse, but suddenly it dropped to the right at knee-level. The batter swung.

Ditch looked over his shoulder as the second baseman scooped up the ball and lazily tossed it to first for the third out. He was out of it. He tugged his cap, maybe to acknowledge the smattering of applause, and walked to the dugout. He was vaguely aware of the fielders passing him, some smacking him on the back, some not, as Holforth appeared at his left elbow. "Told you," was all he said, then found his place on the bench. He passed his manager on the steps. Collins pretended to be absorbed in pitching charts. Whatever, Ditch thought. He found his jacket and shoved his right arm into the sleeve. The end of eight. Maybe he would get through this after all.

One of the starting pitchers approached from the left side of his peripheral vision: the tallish Hansen, the deposed starter of the day. Hansen looked tired, but not beat. He held a cup of water, and nodded towards the bench. "Mind if I sit down?" he asked. Ditch shrugged, watching a Wildcat batter, the first baseman Reynalds, take a hefty cut at an eye-level pitch. After Reynalds would come a second-string outfielder, Williams or something, batting as designated hitter in the pitcher's place. He was glad he didn't have to bat, the only good thing about the minors.

The kid sat down with a contented sigh and took a sip from his Gatorade cup. "Hey, you want any water?" he asked.

Ditch shook his head. "Nah."

"Lemme get you one." The teenager was up and at the cooler before he could say anything else. He opened his mouth and shut it after a moment. Why not, he thought. Doesn't really matter. Reynalds swung mightily at a pathetic curve and topped it back to the pitcher. Just one more run, he thought, no, make that two, or three. He moved forward, resting his elbows on his thighs as he pulled his cap off and worked the rim.

Hansen walked over and handed him a paper cup with rosin-stained fingers. The chalk clung to the green cup as Ditch mumbled a thanks and took a small sip. Hansen sat down again with a thump and said nothing for a moment. The DH was at the plate, wildly swinging at anything near the strike zone. Ditch sighed, thinking that maybe he should be allowed to bat for himself.

Hansen finally spoke. "Thanks for getting me out of that jam."

Ditch was silent. What jam? Oh, yeah, he remembered, he had inherited the first runner. He turned to Hansen. "Sure thing. I didn't help myself with that walk, but...yeah, sure."

"Hey, you're saving my game for me, right?" Hansen paused to finish his water and toss the cup aside. "I owe you one."

"You don't owe me anything," Ditch mumbled. "It's my job."

Hansen was quiet. The DH finally connected — luck, Ditch thought — and hit a worm-burner past the shortstop for a hit. Now one of the outfielders was up, somebody, he didn't know his name. All he hoped for now was that the batters took a few pitches and gave him a little more time to sit. The next batter swung at the first pitch and popped it straight up to the catcher. Ditch hung his head and spit at his feet as the third baseman Corrales took his turn batting.

Hansen coughed into a fist and shifted on the bench. The batter was taking his time. Ditch hoped so. Corrales was their "star player," according to friend Grant. In the on deck circle, Holforth was taking his practice swings with his chest protector and shin-guards on. Ditch sat back and pulled his glove on, half-heartedly to head back to the mound. "Hey, Ditch," Hansen began. Ditch didn't take his eyes off the field. "Uh...some of the guys were thinking of, you know, hanging out after the game," Hansen continued. He shoved his hands into his pitching jacket and banged his cleated feet against the concrete floor of the dugout. He had knocked the dirt from his cleats the previous inning, Ditch noted. Hansen cleared his throat. "You know, like go out to a movie or something. You wanna, I mean, if you want to come with..."

Hansen let a breath out slowly and stopped kicking. Ditch finally looked over at him. Jesus, he thought, the kid was actually nervous just talking to him. "Yeah, okay, sure," he said. Hansen looked at him, then lowered his head and resumed banging his shoes. "Maybe we could hit a bar or something first, you guys don't mind.

The sharp crack of the bat cut off Hansen's reply. They both looked up to see the ball soaring straight up, a routine infield fly. The opposing team's shortstop didn't have to move as he gloved it.

"Well," Ditch said, dropping his jacket behind him, "back to work." He heard Hansen's voice say "...one, two, three..." as he bounded out of the dugout. He glanced over his shoulder and saw Hansen get to his feet and show signs of pacing. Ditch reached the mound and, stooping to pick up the ball, immediately dug at the seams with dirty fingernails. He mopped off a sudden downpour of forehead sweat and looked back to the dugout. Hansen was sitting again, his face buried in a hand towel.

Ditch waited until the first batter of the ninth slowly stepped in and paused to dramatically spit and flutter his bat menacingly. The crowd murmur rose and fell in waves as he readied for the signs. He wanted this game, he realized suddenly. A fine time to get sentimental, but he wanted to win.

Well, then, he thought, rearing back for the pitch. Here goes nothing.

About the author:

Originally from Troy, New York, M. Thomas Apple spent part of his childhood in the hamlet of Berne, in the Helderberg escarpment, and his teenage years in the village of Warrensburg, in the Adirondack Mountains. He studied languages and literature as an undergraduate student at Bard College, creative writing in the University of Notre Dame Creative Writing MFA Program, and language education in a Temple University interdisciplinary doctoral program. He now teaches global issues and English as a second language at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan. Approaching Twi-Night is his first novel. A non-fiction book of essays about parenting and childcare (Taking Leave: An American on Paternity Leave in Japan, Perceptia Press), is scheduled for publication in late 2015, followed by a collection of short fiction and poetry (Notes from the Nineties) in early 2016. The lead editor of the bestselling Language Learning Motivation in Japan (Multilingual Matters, 2013), he is currently co-editing a non-fiction educational research book, writing a science fiction novel, and outlining a baseball story set in the Japanese corporate leagues.

Originally from Troy, New York, M. Thomas Apple spent part of his childhood in the hamlet of Berne, in the Helderberg escarpment, and his teenage years in the village of Warrensburg, in the Adirondack Mountains. He studied languages and literature as an undergraduate student at Bard College, creative writing in the University of Notre Dame Creative Writing MFA Program, and language education in a Temple University interdisciplinary doctoral program. He now teaches global issues and English as a second language at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan. Approaching Twi-Night is his first novel. A non-fiction book of essays about parenting and childcare (Taking Leave: An American on Paternity Leave in Japan, Perceptia Press), is scheduled for publication in late 2015, followed by a collection of short fiction and poetry (Notes from the Nineties) in early 2016. The lead editor of the bestselling Language Learning Motivation in Japan (Multilingual Matters, 2013), he is currently co-editing a non-fiction educational research book, writing a science fiction novel, and outlining a baseball story set in the Japanese corporate leagues.But with every journey, there comes a price; and in every paradise there lurks a temptress. For David, will his quest for excitement lead him to betrayal and loss?

Description:

Published: May 28th, 2015

Be Careful What You Wish For…

What if you had the chance to relive your twenties the way you really wanted them to be?

Thirty-nine-year-old David is presented with that opportunity by Lucien, a charismatic young Englishman. Ranging from downtown Manhattan to Istanbul, Majorca, and the Hamptons, the two of them live a life of excess—drugs, beautiful women, and adventure—and forge a strange but great friendship.

But with every journey, there comes a price; and in every paradise there lurks a temptress. For David, will his quest for excitement lead him to betrayal and loss?

"Wynn immerses readers in psychologically rich studies of his characters and their quiet but fraught interactions. The prose is subtle but vivid, intellectually engaged but never arid, as the author provides readers with a flurry of glittering snapshots that gradually coalesce into a picture of tarnished longings. An engrossing and vibrant...meditation on friendship and the deep currents that run beneath its surface." - Kirkus Review

GUEST POST

Why Book Covers are So Important

For me the two key things a book cover should do is catch the viewers eye, and intrigue the viewer enough so that he or she picks the book to see what it’s about. After that, whether the viewer proceeds to become a purchaser and reader of the book will turn more on the essence of the work, or as much of it as can be gleaned from a quick perusal, and at that point the essence of your book will have to stand on its own.

One thing I have done to increase the effectiveness of my book covers is to have postcard-size copies of them made (with appropriate marketing text on the back), and then at some kind of casual gathering, randomly ask people if they read books. If they say yes, then I hand them the postcards for my two books, and suggest that they give them a try, that they are interesting reads.

About the author:

Danny Wynn is a full-time fiction writer, and before that, he was an executive in the record industry and part-time fiction writer. He has lived in New York City, Los Angeles, and London, and now makes his home in the West Village with his wife and two children. His other favorite place in the world (after the West Village) is the island of Mallorca, Spain

Danny Wynn is a full-time fiction writer, and before that, he was an executive in the record industry and part-time fiction writer. He has lived in New York City, Los Angeles, and London, and now makes his home in the West Village with his wife and two children. His other favorite place in the world (after the West Village) is the island of Mallorca, SpainHe is currently finishing two novels.

Danny describes himself as a creature in search of exaltation. In addition to attending the original Woodstock Music Festival, some of the other great concerts he’s been to include: Roxy Music on the Avalon Tour at Radio City, Bon Iver at Town Hall and subsequently at Radio City, The National at BAM and later at The Beacon, and The Waterboys at the Hammersmith Palais, Bruce on his solo tour, U2 on Zooropa and later tours, Dylan on the right night, and Van on the right night.

Among his favorite movies are: Performance, Bad Timing, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and Withnail and I. His favorite novels include: The New Confessions by William Boyd; A Flag For Sunrise and Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone; The Magus by John Fowles; Legends of the Fall by Jim Harrison; andThe Comedians and The Quiet American by Graham Greene.

He derives enormous sustenance from his close friends.

Joe Zizzi's childhood in the 1950s had everything a kid could want--pro athlete dad, wonderful mom, cool big bro. When the '60s kick in, this ideal life is violently shaken:

Description:

Joe Zizzi's childhood in the 1950s had everything a kid could want--pro athlete dad, wonderful mom, cool big bro. When the '60s kick in, this ideal life is violently shaken: a car crash claims his mother's life and his father's career, and brother Matt becomes distant and disturbed.

Over the years, Joe learns to cope and carves out a niche for himself as a college sports star, and later as a coach and writer, but he can't quite shake the family legacy. Diagnosed with kidney failure, the semi-pro husband and devoted dad has life-and-death decisions to make--and life wins, though perhaps only by a slim margin.

EXCERPT

It can’t be possible. I can't possibly have PKD. Dad wasn't symptomatic until he was about seventy or so. Here I am, I'm not much past fifty and here I am. I know with the spring term being on, I had to start coming out with it. I told the players about my condition. I’d done this in the fall also, telling them I wasn't well, but this term I told the kids the first meeting, complete with the official name for the thing. I told Sr. Frances about my condition. I told Father Arsenio about my condition. The word gets around, and the parents are all talking to me. My colleagues are beginning to avoid me. I sense distance once I let them know what was happening and the word starts getting out.

I'm on a low-protein diet, and I'm fatigued, having trouble sleeping. Between the low-protein and the little sleeping, I'm in a lot of trouble. An opposing coach catches me looking like I’m nodding out at the game. The opposing team is snickering. The kids win it for me; I’m the human interest story. They've probably never seen classic movies in their lives, but they're winning for me—the coach needs an operation! The kids are of course involved in normal real-time culture. They've named me J-Ziz and I accept it as the awesome name that it is. They worry about me. They want to know about the food restrictions. Sometimes I'm busted when they catch me eating the bad stuff in my office, which I do on a regular semi-regular basis. My standard speech is, “I'm not going to be one of these ‘do as I say, not as I do’ types with you. I'm on the straight and narrow a lot. But it's taking some getting used to. I gotta fall off the wagon sometimes or else (a) I'm not going to be human, and (b) I'm not gonna be happy." I'm entitled to this dog or murder-burger or whatever.

As a kid growing up in New York, I was always in some stage of writing, even if it was only the making-stuff-up stage. I grew up with long-ago tales of authors strolling into a publisher's office, wowing them with a manuscript, closing the deal over a pricey lunch, and becoming a celebrity--imagine my surprise finding out that it doesn't work like that now, and it hardly ever happened then! After gathering a large enough stack of rejections, I went back to making stuff up, but when I was diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease, I returned to writing. I wrote I, Kidney to empower people with chronic kidney disease, educate the public, and raise the awareness of health care providers, who can easily lose sight of the patients. I meant to get the book out in 2013, but my transplant put that on hold...until now.